Community Stories

Below are a few stories from the different people and groups we spoke to during our research on their work and how their communities are interacting online.

Meetups and Conferences

It was late February 2020, and Andres Colmenares and his collaborator Lucy Black-Swan had less than three weeks to turn their IRL weekend-long conference and festival, IAM, into a digital experience. The conference, now in its sixth year, looked to critique technology and create a gathering focussed on learning, fun and critical engagement for technologists and artists.

Presented with the challenges of moving the festival into the online space, this digital event now relied heavily on the tools that it originally had intended to critique. The goal with IAM was to provide intimacy and grounding for creative thinkers to question and push technology to new places, providing necessary criticism of the tools that technologists use, questioning, and how to improve technology and limit big tech’s reach. But the space is really about intimacy and knowledge exchange - it’s about meeting people and engaging. Could they create intimacy online? Should the conference even happen online?

It was a Catch 22 for Colmenares and Black-Swan. Colmenares and Black-Swan decided to try, and individually emailed the speakers and the over 300 attendees about this shift to a digital platform, offering refunds and gauge what changes people were comfortable with. The result was positive - people wanted to come. But Colmenares and Black-Swan knew that for IAM to be successful they needed to do something beyond streaming, and they only had three weeks until the conference dates to do it. Colmenares and Black-Swan are researchers, producers, and creative technologists, so they had the creative knowledge of how to push conferencing tools to make something interesting. They also had cultural timing on their hands.

With the rapid onset of a public lockdown in the wake of COVID-19’s spread across Europe, people were scared and confused, but also determined to show solidarity and engage with the community. IAM’s organizers wanted to create a remote event as opposed to one which was purely ‘digital.’ This shifting was key; by focusing on a remote platform, they were able to use a variety of different tools to achieve greater engagement. Their main talks took place in Zoom, but they also set up Zoom Karaoke events and ‘bodegas’ in other Zoom rooms for people to congregate and have digital ‘coffee.’ They also created an access hub that Colemanres described as “a link archive...it had a graphic interface where people could see what activities were live, what type of activity, and then inside each of those boxes there was a link to a Zoom room that we also had a team working in the back stage setting up all the Zoom rooms.” A Barcelona-based Iranian artist, Mohsen Hazrati, created a VR experience of their room in Shiraz, Iran, which was then represented in VR to participants. Colmenares said, “It was the first time that a VR [project] made me cry.”

Colmenares and Black-Swan decided to use Zoom as the central platform, making transparent available all the different places people could congregate for IAM, as well as making the schedule as easy to follow. Meetings feel different inside of video conferencing; spontaneity doesn’t exist in the same way - there are no coffee tables or hallways to have conversations. Creating a digital space to mirror those interactions was key. This is why having a specific plan for this space is critical. IAM built separate software for people to access these links, but not everyone needs to have such a high level of programming knowledge. Organizers can use something as simple as a Google Doc to achieve similar results.

Creative Mornings NYC did something similar. Carly Ayres, a Google Creative Strategist, described Creative Mornings as encouraging participants to be active. "Turn your camera on. Being part of this event you have to engage. You have to participate.” The organizers aimed for an event that was equally fun and accessible, so they changed their names to include emojis to mimic the way organizers in offline events will wear distinct shirts or lanyards. They recreated the traditional ‘coffee break’ over video, pairing up the over 400 participants in groups of two over Zoom breakout rooms. Creative Mornings didn’t require a technically heavy event, instead using pre-planning, a clear event structure and activities to create an engaging event. One of their organizers, Alexandra Kutler, even created a robust but practical guide to setting up Zoom calls that we feel is very useful for prospective organisers.

The exhibition design of a space doesn’t just stop at the tool choice; it’s also thinking through the choices and activities attendees will be engaging in. IAM had a Buddhist monk lead a ritual to begin an event, and explored group karaoke over Zoom. Sacred Design, a research and design consultancy, created a series of best practices called “Ritual Design” for one of their spiritual meetings, Family Chapel, to help hosts use repetition and ritual in virtual settings.

These best practices, written by Angie Thurston, Sue Phillips, and Casper ter Kuile, illustrated findings on creating a guide for hosts and participants in what to expect in the meeting, acting as a syllabus. This outlines what the content of the entire meeting will be, how long activities will take and what to expect in the activities. It is equally important to mark this time by having consistent beginnings and endings to your meetings. This could be achieved with a specific kind of greeting or gesture, asking the same question (“how was your week, what was something special that occurred, et”) or lighting a candle.

Colmenares suggests the best way to create positive engagement at an event is to address the central questions of why the organizers have chosen this specific event, and why it is the right event for the intended community or audience. In answering these questions, the organizers can determine which tools and what spaces are the most effective. By focussing on “people first and the tools second” Colemanres emphasizes the need to “treat and think of the members of a community as citizens. Both with rights and responsibility, rather than as users.”

Educational Spaces

“There hasn’t been a moment to take a beat,” University of Texas professor and author Simone Browne explained over Google hangouts. Given the urgency of the moment, it overrides questions we should be asking about tool adaption or how faulty these tools can be. We aren’t asking “what's the worst-case scenario [in] similar technologies.” Browne is talking about the deeper, more national and global shift to quickly adapting video conferencing technology. People have hadn’t a moment to stop and ask what kind of harm this creates or what the tradeoffs are.

Shifting to Zoom is a bit of an educational mandate, meaning if a university or school picks this software, teachers and students are obliged to follow suit. There isn’t a space to divest from what the institution picks. Yet institutions don’t necessarily have the bandwidth or expertise to predict what is the best online learning set up, instead quickly creating ad-hoc solutions to get students online as quickly as possible. Teaching on Zoom is different than speaking at a conference. Teachers lack feedback from their students from the tool, aren’t getting clear indications of the latency or internet connectivity from students, and no clear feedback if their own audio or video has paused, glitched or lost connection. Pamela Liou, artist and educator, echoes this, “Syncing makes it basically impossible to teach... I signed in twice to the Zoom so I could have one screen-share on my Mac and one screen share on my PC. So my students are chatting with me, they're typing in questions to the wrong chat.” Zoom didn’t provide the resources to make this a possible way of teaching.

A deeper challenge designers face is not a technical one but a human one, beyond the control of schools. What is the students’ home set up? Are they comfortable? How is their internet connection? What timezone are they in? In an effort to address these concerns, the alternative school The School for Poetic Computation (SFPC) tried to create a clearer workflow and structure for students. Lauren Gardner, co-organizers of SFPC, created workflows for both teachers and students and using tools like Google Calendar, DropBox, Google Docs, and Slack outlined what documents are stored and where so as to make the navigation of remote learning easier for students and teachers. SFPC actually built their own software to centralize this with a former student, Bre Pettis, a few years ago. Skill School was created because “we wanted a tool that was free, and it's a mix of GitHub and a learning CRM. And the idea is that as an instructor, you can either open-source your classes on there, or you can lock them down, but it's a way for you to create your curriculum and then fork it or allow other people to fork it and build stuff.”. SFPC is hoping to shift back to Skill School at some point (the school hasn’t put it into use during COVID19, needing to respond immediately to lockdowns and rely on on-hand tools that their students were already comfortable with.)

Skill School still needs some improvement to fit their teachers' needs, particularly those that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Garnder and her teachers need a better way to explore students' work which is spread across multiple websites. One design idea would function almost like a gallery or dashboard, creating a way to see student’s updates and progress on platforms like an Are.na board, Github pages or Google Docs.

As Browne mentioned during our conversation, these tools, and especially their data privacy policy and the politics, need to be critiqued and analyzed. This is crucial as Zoom recently announced the removal of end to end encryption in it’s free software to better collaborate with police departments. This kind of privacy concern is what Browne’s work focuses on. But Browne has also another concern, namely the lack of ‘design’ in a digital classroom space. Where and how students chose to sit and organize themselves can be a reflection of creating safer spaces in a classroom. “I teach a class, probably 150 students. Why should [the students] have to do a unit where you can make decisions of who you want to sit next to, who you want to hear. Should you be able to mute certain people out of the conversation just like everybody joins in [similar to Twitter]. But maybe I actually just don't want to care what this person says in the same way that we can.”

Browne raises further questions; “What does safety look like in those spaces when you are basically letting these people into your home in a way, ...who you didn't bargain [with]. Like they bargained to be in a class when they decided to be in conversation with the professor in that home, but they didn't bargain to be in class with some of these other people that could be just there to fall or to be hostile.” Enterprise software is rarely designed as well as consumer software, a sentiment echoed by Garner (who worked in enterprise software before switching to education), but if these tools are going to be used by schools, they need to reflect the teachers’ needs as well as those of the students. What does safety look like in a big classroom which acts as a community, an ecosystem and a space of constant engagement, of friendship building, of difficult conversations and a place of even potential harassment? What does safety in design look like then?

Artists and Individuals

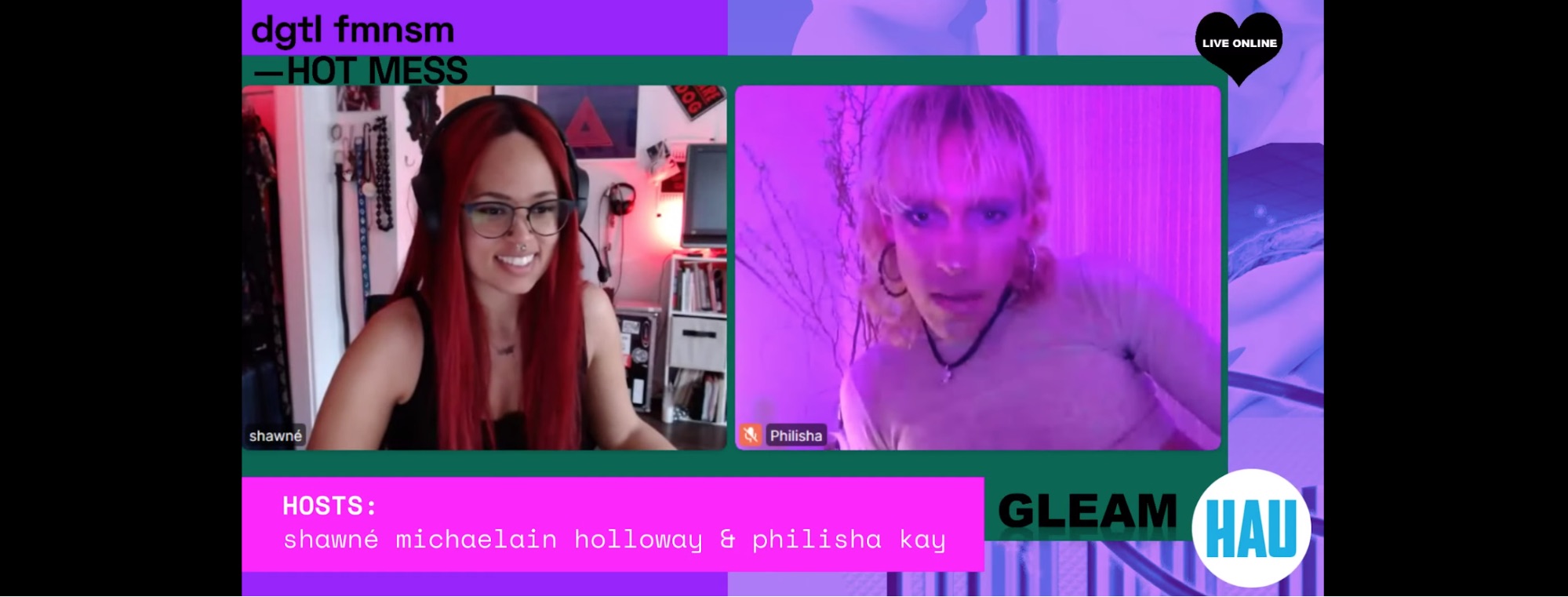

“When COVID-19 hit, it led our program back online and to us using our hardware for, well, survival,” artist and educator shawné michaelain holloway describes her four-year-old online streaming project, GLEAM. “Gleam LIVE ONLINE has always tried to push and study online performance methods. [COVID-19] has tested the limits of our computing power, for sure, as well as our ability to connect and entertain. Previously our program had elaborate stages and physical choreography for viewers.” Now the project has returned to its original form of just live streaming.

Artists and individual creators are presented with an interesting challenge during COVID19, of adapting offline talks for solely online spaces, turning performances into digital streams, or crafting intimate workshops across video channels. How can one yield to intimacy, and create intimacy and creating engaging art? It requires understanding and awareness of the medium itself, something that technology-based artists, such as holloway, understand very well.

In 2016, holloway created GLEAM, an after-hours talk show on Youtube, focused on conversations and video art pieces between featured writers, artists and creators. This invaluable experience allowed Holloway to prepare for a move towards increasingly digital platforms in the face of COVID-19. The show’s success lies in holloway’s ability to hone and perfect this format, which is carefully planning short time limits for talks with multiple artists and embracing different kinds of content from pre-recorded videos, to live presentations and Q&As). holloway emphasizes the need for careful planning, saying that by “...being the host, I run a pretty tight ship in terms of running order, I know that I want to get through everybody and everything in the time that you might want to watch a movie. That's the experience that I'm looking for from online presentations. I don't want to hear your news. I want a program.''. She also highlights that when working with artists who appear on the show, she either gives them bullet points for discussion or a time limit, allowing the artist to fill in the rest.

Whatever the artistic medium is, be it a performance, lecture, panel or any other livestream video performance, rhythm and timing is critical. The digital space is difficult to navigate because many of the tools offer no feedback and audience engagement is fundamentally different. “In an online environment, you need to be even more restrictive with it because of people's attention span,” holloway explains. Prem Kristhnamurthy, a graphic designer and curator, takes a similar path in his Present! Performance lectures, which over their two hours have a variety of tempo and rhythm, lectures, karaokes, and meditation. The time limit on each ‘event’ or exercise inside of the experience is key. This, Krishnamurthy says, is because “...time on Zoom feels twice as long as normal time.”

One of the larger challenges facing artists creating online is figuring out how to articulate their vision or statement while balancing enjoyment for the audience and maintaining engagement- the thought process is similar to running a theatre show. By having a running schedule and a plan, creators can work through the drawbacks of digital presentations, such as an inability to quickly recognize audience fatigue, working through of not knowing what the audience sees, not getting direct feedback, and having to test and test and test the tools so they work for show or event when it launches. Fiona O’Grady, a creative producer who created karaoke sessions for the conference IAM, says as the creator you have to limit your experiences for the enjoyment of your audience. She explains that “if someone wants to perform, then at least everyone else hears it at the same tempo as them, so they get their time to shine. So as a host, I forfeit my time to shine for other people's chaotic good audio experience.”

In our discussions, Kristhnamurthy brought up the idea of reconfiguring expectations. Online performance lectures are a different kind of medium, and the audience interacts with a screen differently than a regular. There may be similarities but you will still have to yield to the limitations of the medium or at least incorporate them. holloway echos this, saying “I think interaction design doesn't stop with interfaces either. And, my work is completely about that specifically through the lens of performance.” Artists, before this moment, have been using technology as a means to comment on technology, but that doesn’t always mean the tools work well for them to show their work.

Online Creative Spaces

“What if we held a field trip inside of a videogame?” This question was the premise for a virtual exhibition called Now Play This!, a video games and interactive arts festival in London which had to move to a virtual space due to the UK’s COVID-19 lockdown. Marie Foulston, the curator of the festival (and former curator of games at the Victoria and Albert Museum) has been thinking about what curation and exhibition design “means” in a digital space. Festivals, arts institutions and community spaces are facing this emerging problem- designing spaces online that have traditionally existed offline. Looking at a painting on a gallery wall is now suddenly a digital experience. Exhibition design, even in digital spaces, matters. It is not enough to simply upload an image to a website. We must design our websites to function as art spaces.

Now Play This! festival is traditionally a very physical exhibition that uses a historical building in London and utilizes space in a particular way. But Fouldston wanted to rethink what online exhibition design meant. These included videogames ‘field trips’ where a creator teaches landscape photography in No Man’s Sky or a detailed and analytical walkthrough of Half Life 1 with games developer and professor Robert Yang. These events were followed by panels in Animal Crossing, artist lectures on Twitch, and showcasing digital art on the event’s website. Now Play This! capped the number of active participants to ten to focus on the audience's engagement in the field trips, though they did live stream the event. These examples show a morphing or reconfiguring of video games, of using beyond its intended purpose to yield delightful results.

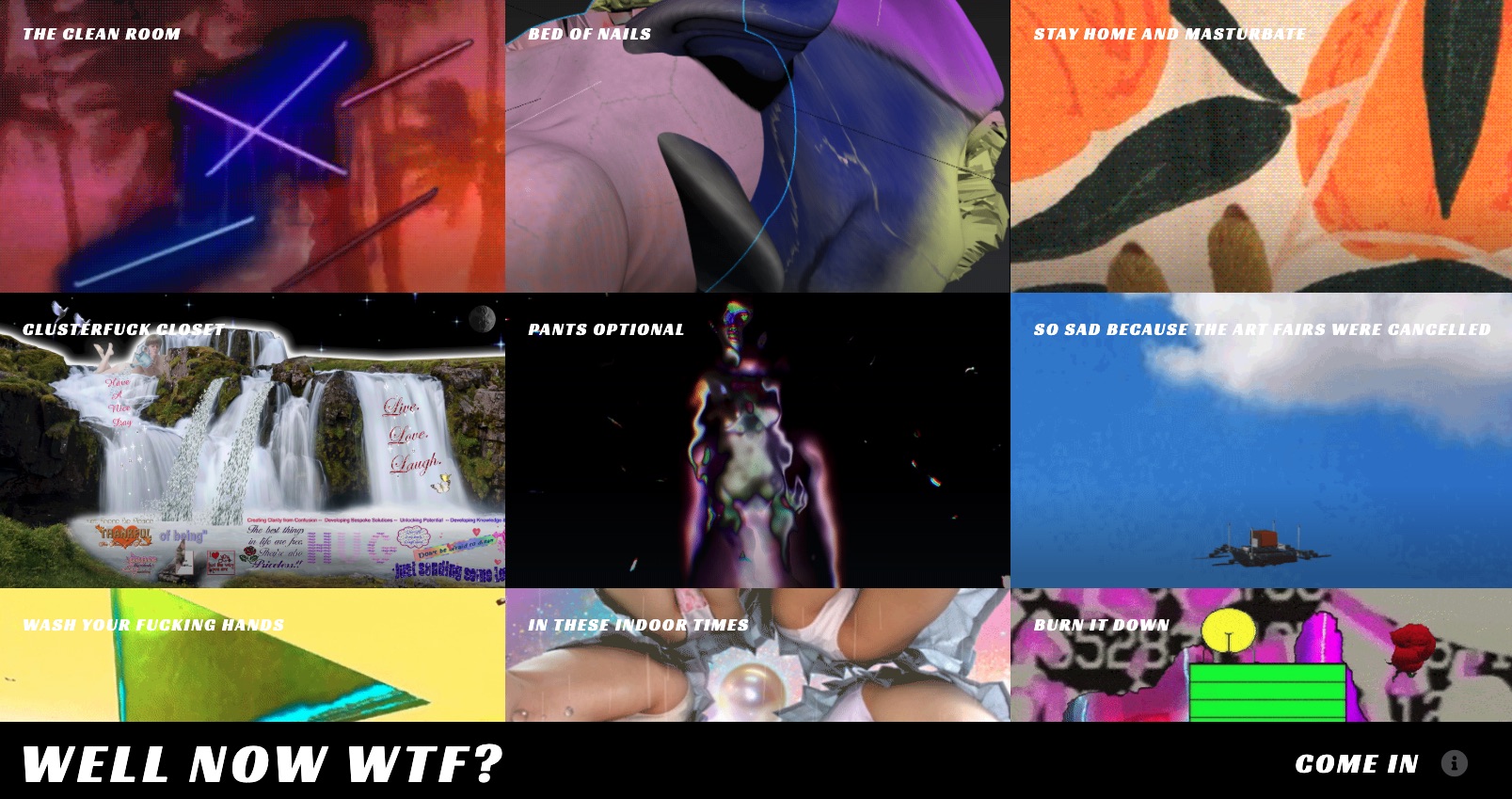

There have been virtual exhibitions, including some taking place in digital-only spaces such as Second Life Michael Connor, the artistic director of Rhizome, an arts publication dedicated to digital art and net art, published a guide to curating online exhibitions which is now particularly pertinent in the time of COVID-19. Well Now WTF is a net art exhibition that features over 90 artists curated Wade Wallerstein and artists Lorna Mills and Faith Holland. The exhibition came together in three weeks and is arguably one of the best exhibitions to be created during COVID-19, having been reviewed in the New York Times, Art in America, Hyperallergic and numerous other outlets. The success of the show seems obvious to the curators - “art’s good and it’s in its native format” explains Holland - but this success is also due to the curators behind Well Now WTF being digital artists and curators who know digital tools extremely well.

Faith Holland emphasizes this sense of breaking new ground, saying “I don't think we really innovated here, but we just knew what tools were going to be available to us and we made use of them. And we made use of them with artists who also knew these tools and knew what it was to put together an online show because yeah, it's just not new. It was the right moment, but it's not a new moment.”

Digital events can often feel little more than a simple broadcast, lacking the intimacy that organisers such as Foulston desire. These events feel stilted, similar to how arts museums are using platforms like Google Arts and Culture to ‘explore’ a museum - despite the intentions, they fundamentally lack the UI to make the visit seem genuine, like walking through Google Maps to visit houses. The rooms in Well Now WTF, their artist talks over Twitch and the Animal Crossing spaces housing art create and encourage user interaction, allowing for engagement in a specific, ritualized way. Visitors have to visit the specific Animal Crossing ‘island.’ The embodiment of that space is different for users than doing it on Zoom or in the case of Well Now WTF, beyond just a regular slide show since all of the content is animated - it moves in a way that regular art does not. The juxtaposition of that space also looks a certain way - in the case of Well Now WTF it’s dark and sexy, and with Animal Crossing the aesthetic is far more twee and cute, but personalized per person. These rituals don’t always translate completely across the two platforms but that’s okay.

Thinking through what an ‘exhibition’ means online, an obvious goal is that it is intentional and fun. Digital content looks good online, it’s designed to be there. And it’s increasingly moving away from a ‘physical’ idea of an exhibition, and leaning into the digital, which is movement based, weird, and strange. Lean into the strangeness of what the content does well.

Mutual Aid Groups

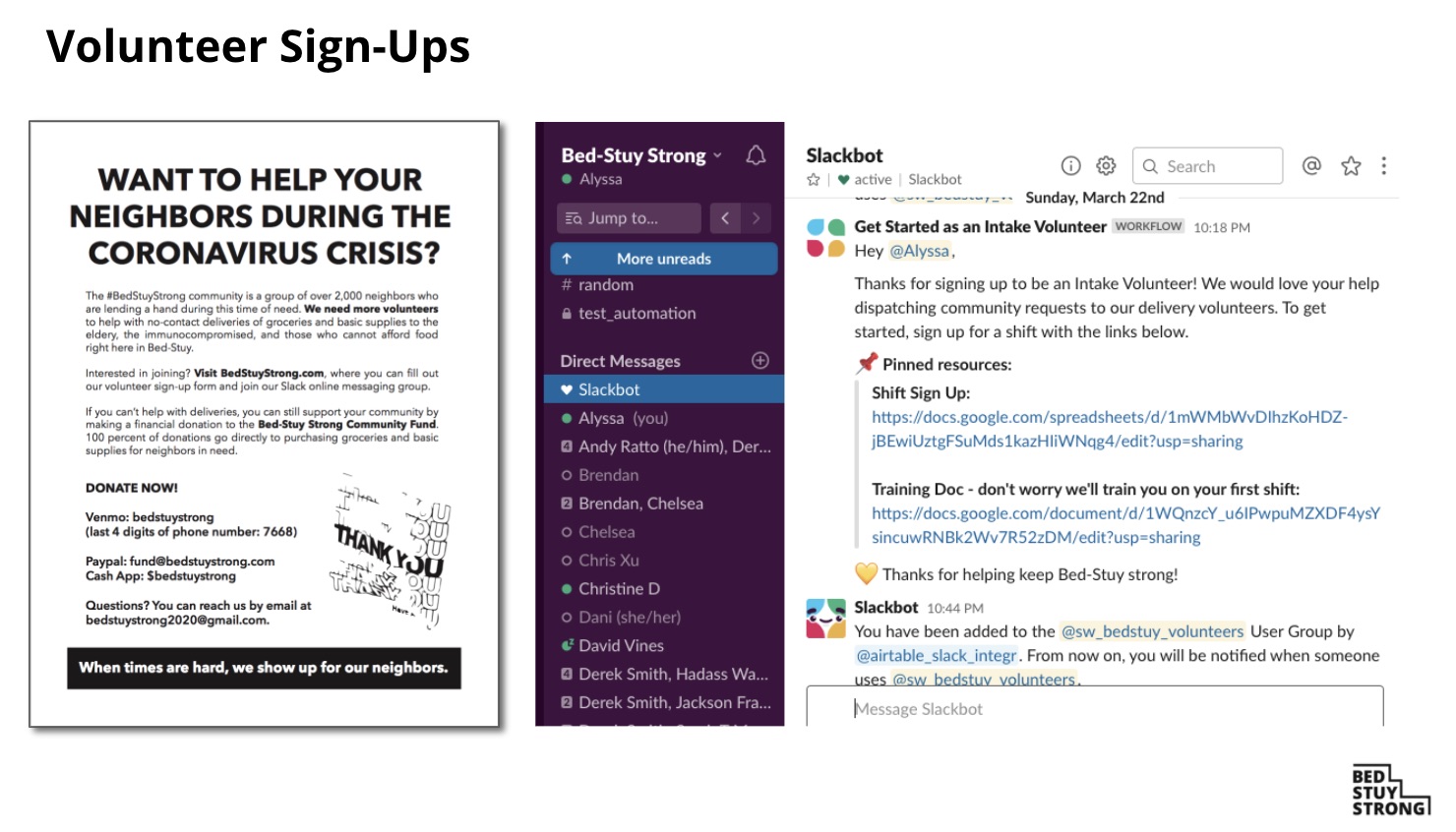

Mutual aid groups are volunteer groups that can help provide supplies, groceries and support during a time of crisis. This community-building effort is able to grow quickly and successfully because the participants are already community builders involved in their community. It was a focus on community, not the individual, that allowed for NYC PPE (previously named Last Mile) and BedStuy Strong to come online. These community ties existed, albeit in less official forms, before COVID-19. The technology sprung up around the communities as people went into action to help each other. These groups are using multiple tools digitally duct-taped together to function, working with thousands of data points and many volunteers, from Airtable to Slack to WhatsApp.

NYC PPE functions because of preparedness and foresight that members had, and some of these key members were Chinese-Americans and Chinese immigrants in the US who were prepared months before COVID19 affected New York. The important thing to realize with these two groups is that the community bonds and building are not something digital created, or could have fostered, but it comes from the participants and greater community itself that already existed.

Xin Liu, an artist and volunteer with NYC PPE describes it’s origins, “Lots of Chinese people I know in New York actually have some stock. So I decided to donate my small proportion to health workers. So I start asking around, hey, do you guys know any health worker who might want like 10 mask and that first contact onto second. And then very quickly it became a kind of a tiny little operation. And there are also people who are waiting to help me deliver. So, that's the first week. And then later it got much bigger. Because there are more donations and more people joining with me. And then many other people join the forces. So it became an actual operation rather than just me and a few friends taking notes on the paper and trying to figure out who's getting what.” This story is similar to the other organizers, each having extra masks or materials. One volunteer started a WhatsApp group and it grew and grew from there. Xin Liu volunteers with NYC PPE to help coordinate deliveries of supplies to hospital and front line workers, by working across Slack, Airtable and WhatsApp.

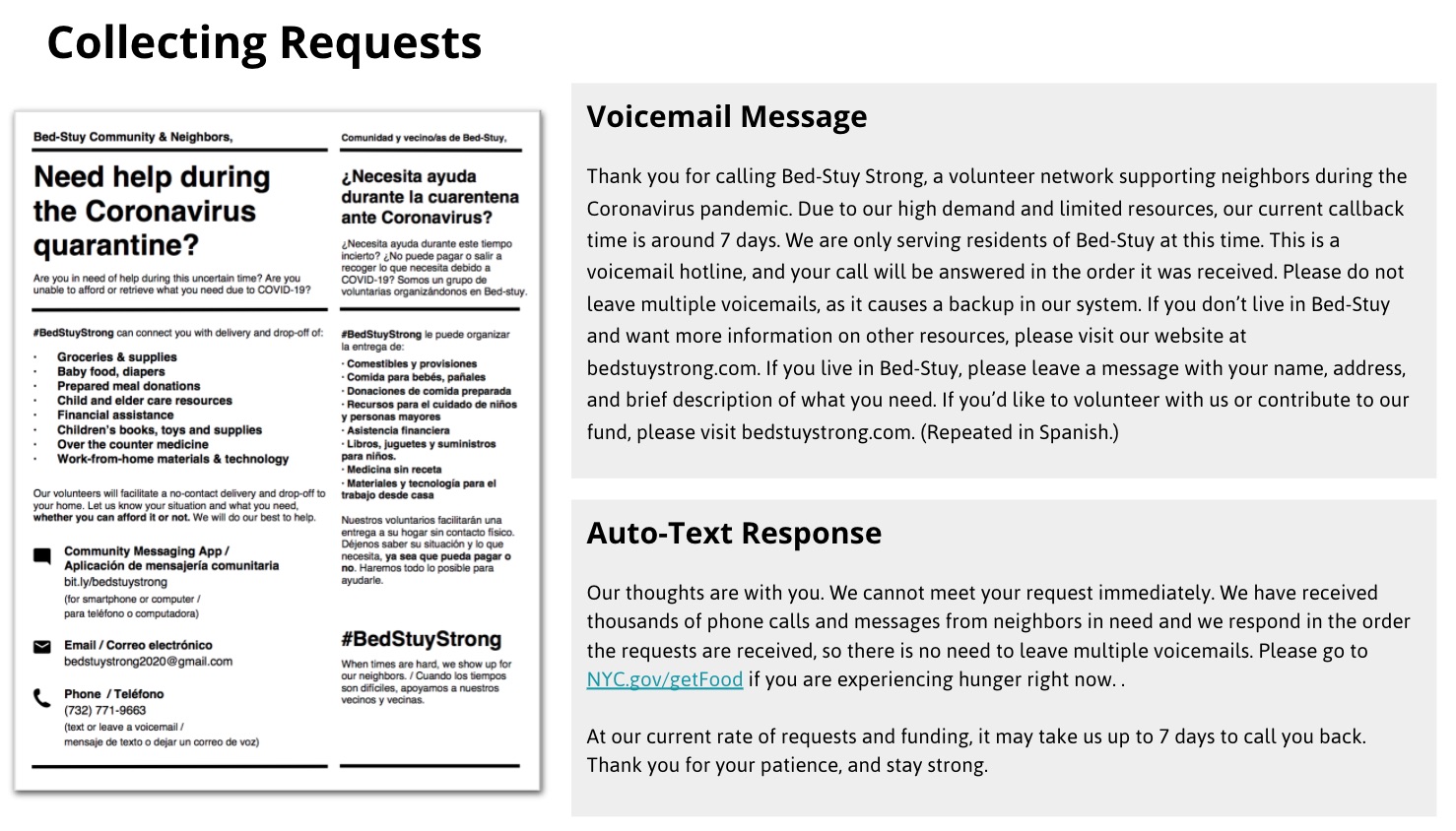

BedStuy Strong is a digital group that sprung up to help the neighborhood of BedStuy support their neighbors during COVID19, with all different kinds of support, like grocery delivery. The group has flyers all over the neighborhood and then instructions on how to join the BedStuy Strong Slack channel to coordinate delivery, create spaces of communication during COVID19, and organize volunteers. They use Slack, Google Voice and Airtable to help organize deliveries. Samantha Garfield, a volunteer with BedStuy Strong gives an example of how the group tries to meet and organize across their nearly 3,000 members. “The other day we posted an all-hands meeting where we were looking to get broad based buy-in on a set of guiding principles for our mutual aid group, and we were struggling with how we can we do that effectively because there might be hundreds of people on the call, and the goal is not just to ask them to thumbs-up, thumbs-down, but to genuinely invite hand-raisers, [all] different levels of possible engagement. So we had a conversation going where we were, A, asking people to Stack in the Zoom chat, B, asking them to weigh in via a straw poll on Slido, and then C, concurrently posting a Q&A on Slido and having people upvote or downvote questions. So there were sort of levels to how people could voice their dissent based on how extreme the dissent was,” outlines Garfield on the workflow.

As an organization, BedStuy Strong created design principles to help guide their group and community:

- No overengineering -- always keep our goals in mind!

- All information needs to be easily accessible by all volunteers.

- Low technical barrier to entry.

- Protect our neighbors’ privacy.

- Accessible for volunteers, for neighbors, for any future leadership team.

- Avoid solutions that lock us into one framework/vendor.

- Systems must be flexible, and composable.

- With every decision - ask for whom, by whom, and with whose interests / objectives in mind?

Even further, they’ve thought about what are the needs of the community, and the pain a community can face. They have milestones and are thinking about sponsorship, and worrying about volunteer fatigue (and trauma awareness). But more importantly, they think through data privacy and what to do when intaking personal information for deliveries. From a BedStuy Strong presentation on data, the community encourages that volunteers realize that “Providing personal information is an act of trust. We treat our neighbors’ personal identifying information (PII) as our own” and that data cannot be shared publicly and must have restrictions around it.

Groups need to think through when intaking information what to do with it, and why. What is the point of their group and what are the solutions? NYC PPE and BedStuy Strong exist to help alleviate big issues brought out by COVID19, but the groups don’t aim to solve all problems NYC PPE is delivering masks and other necessary items, and BedStuy Strong just exists for BedStuy, not all of Brooklyn; they follow their defined missions. What they accomplish is monumental, and they accomplish with dedication, organization, and a focus fulfilling the missions of each group.